By Bill Stark, Copyright August 2012

Post Cards from Bolivia

I seldom think about buying postcards to send to friends and family when I travel. Facebook and other social media sites make posting my photos much easier. My great-grandfather, Hugh Callory Watson, would have benefited from social media. He took photos of his mining expeditions and collected and sent many postcards. What follows constitutes a view into photos and postcards that now share space on pages of photo albums dedicated to his friends and travels in Latin America.

Next to the photos Hugh took while traveling in Bolivia at the turn of the century—images of Cholitas, Quechuas, and Aymaras—there are postcards depicting opulent buildings, plazas, and soldiers parading in front of historic sites. Did Hugh mean to send the postcards? To whom?

My great-grandfather traveled to La Paz, Bolivia, in 1907. Only a few years before, he had graduated from the Colorado School of Mines and signed on with a multinational mining conglomerate out of New York City. He had not yet met my great-grandmother, Mary Margaret Paradise. A mining engineer, consultant, assayer, and mine superintendent, Hugh worked in Central and South America and Mexico at the beginning of the 20th century.

The frayed photo above shows three women walking on a cobblestone street by an open market in La Paz. A woman stands, chin in hand, in the entrance of her shop, her goods on display for passersby. Two other figures, toting large, cumbersome bags on their backs, occupy space behind the three central figures. The inscription in the upper left-hand corner of the image tells the viewer that the scene is in La Paz, while the rest of the inscription is illegible. Nevertheless, the photo provides detail about commerce and aspects of daily life in La Paz at the turn of the century.

I visited La Paz nearly a century later. We arrived in a two-engine airplane, which afforded us a view of the massive bowl in which La Paz sits. The edges of the city are riddled with abandoned old mine shafts. One of the national capitals of Bolivia, La Paz sits at the bottom of a deep canyon on the Altiplano at an altitude of 11,942 ft (3,640 m). The city itself, I recall, exhibited a surreal combination of modern commerce, including McDonald’s on every other corner, Domino’s Pizza, and Starbucks, mixed with turn-of-the-century buildings constructed with cast iron, appearing to hold the Earth down wherever we saw them. In the center of the city, there is a large, smoky open plaza where Cholas gather to sell potatoes, vegetables, and other goods: the Plaza Mayor. There are open-air stalls that sell chorizo sandwiches and delicious soups and stews. I ate some of the best food in South America in that plaza. The produce was amazing. The people were friendly, eager to interact, to sell.

The photo below shows a Cholita wearing the distinctive bowler hat, layers of long puffy skirts, and a thick poncho draped over her jacket. When I was in Bolivia, Cholitas were still dressing the same way.

In the photo above, a group of men, women, and children have dressed for a photo. At the entrance, in front of a clothing store, the group is seated and standing, a fully dressed mannequin directly behind them but seemingly part of them. On the left, in the middle ground behind the woman, a little hand is attached to a faded arm and a blurry head. A ghost? Or a fidgety kid?

My great-grandfather learned Quechua while working in Bolivia. He was a gregarious soul who liked to talk with people.

Native Aymara.

A Collection of Postcards from Bolivia

In Hugh’s collection of postcards, there are black-and-white photos like the one below, and many others modified with color.

The Bolivian Army, the 1st Infantry on parade in Murillo Plaza, La Paz.

Guaqui, Bolivia, is a railhead and port on Lake Titicaca, the highest navigable lake in the world. This port connects with Puno, Peru, via a ferry (car float).

Although Bolivia is a landlocked country, Lake Titicaca is home to the Bolivian Navy. Before the War of the Pacific (1879) with Chile, Bolivia had access to the Pacific Ocean via the Port of Antofagasta. Most of the original fleet of ships arrived at Lake Titicaca piece by piece via mule train from the Port of Antofagasta. Most of the materials for the ships came from Great Britain.

After making their way to the Port of Antofagasta, they were carefully transported by pack mule via steep mountain trails to Lake Titicaca, where engineers then reassembled the ships. Once the coal ran out, the ships were modified to burn llama dung.

Lake Titicaca is also purportedly the home and birthplace of the Inca. La Isla del Sol is said to be the site of his birth. There are several ways to get to this island in the middle of the lake. I traveled southeast from Arequipa, Peru, to the city of Puno on the northwest shore of Lake Titicaca. From Puno, direct bus routes link Puno to Copacabana. Copacabana is an international haven for young, hip travelers that sits on the southeastern shore of Lake Titicaca. There are restaurants, hostels, internet cafés, and some of the coolest, hippest lounges and bars in Latin America.

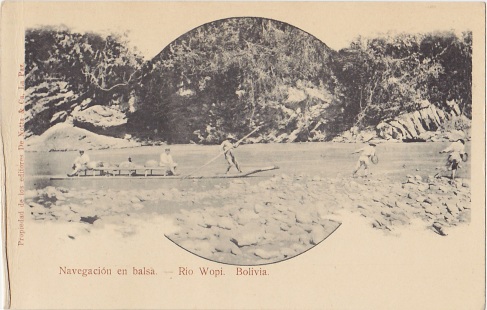

Balsas are still in use on Lake Titicaca to this day.

As I mentioned before, La Paz is an amazing city that sits at the bottom of what appears to be an enormous crater. And, while it is possible to see the scars that mining has left upon the city, it is a city of refined charm, with elegant 19th-century architecture and broad boulevards that bustle day and night with commercial and cultural events. As this photo of my great-grandfather’s friend, violinist Molly Pierce-Hope, suggests, La Paz was a center of haute couture at the turn of the century. The opera house was one of many architectural landmarks built to attract more Europeans to Bolivia and to show that an appreciation for the arts existed in the rugged New World.